Earlier this month, the closing ceremony for the 2024 Summer Olympics was held in Paris to considerable fanfare. You may have watched the very French opening and closing ceremonies, or any of the athletic competitions that occurred between them over the span of two weeks. Those of us stateside were able to watch Olympic athletes break world records and set personal bests because an American network broadcast their events on our televisions. If you tuned in at various points, you probably saw the inspiring TV commercial the network ran to trumpet the importance of playing, at all ages and stages of life. It ended with this tagline: “A Little Joy Goes a Long Way.” Whether the Olympics brought you and yours a little or a lot of joy this summer, there can be no doubt that joy goes far. In fact, it can travel around the globe almost instantaneously.

We should never underestimate the power of joy in any season or year. And yet, too often, we do. American gymnast and gold medalist Simone Biles expressed gratitude that the Paris Olympics gave her the chance to rediscover the joy she had originally experienced on the balance beam and uneven bars and throughout her high-flying floor routine which for obvious reasons seems terribly misnamed. This has made her a better sport overall, someone who loses as graciously as she wins, because she is just that glad to be back in the arena. She spoke to journalists of the “pure joy” that her athletics is again bringing her. I believe that knowing joy, expressing joy, and sharing joy should all be counted as victories in their own right, and that beyond that, they fulfill a crucial spiritual imperative that several religious traditions issue us humans.

Last August, when my father-in-law died unexpectedly in his sleep, my husband Ben and I flew to Cincinnati and attend the memorial service at his synagogue there. In September 2023, the two of us joined a local temple in suburban Boston so that we could have a place to say Kaddish in his honor. In October 2023, Israel suffered a terrorist attack during the festival of Simchat Torah, the Jewish holiday with the Hebrew name that literally translates as “rejoicing in the Torah”, which annually celebrates God giving the people their most sacred portion of scripture.

On any given Friday, those of us at Temple Beth Elohim are busy. We are praying for peace to be brokered in the Middle East, even as we are holding our hope for the release of Israeli hostages. We are sincerely wishing each other “Shabbat Shalom”, the peace of the Sabbath, even as we remain painfully aware of violence and injustice and atrocity around the globe. We are supporting the mourners in our midst by saying Kaddish each week in memory of the loved ones they have lost only a short while ago, even as we are congratulating families bringing their young children to the bima to receive their Hebrew names with rounds and rounds of “Mazel tov!”

In all that busyness, in the midst of powerful mixed motions, what’s most obvious to me is the joy of our communal worship, the sounds of our voices lifted in songs of praise and thanksgiving, despite everything. Week after week find ourselves echoing the sentiment of the Psalmist who declared, “You make us glad by your deeds, O Lord; we sing for joy at the works of your hands!” The rabbis there have been criticized for this communal mood. During such dark times, how dare we welcome Shabbat with such jubilation in our evening services? In response, the senior rabbi is wont to repeat the teachings of ancient Jewish sages contained in the Talmud: if a funeral procession approaches an intersection at the same time as a wedding party, they say, it is under holy obligation to give way and let celebration go on ahead. We had a similar notion in the Catholic Church where I was raised, summed up in the rule, “feast trumps fast.” Any time that a feast day and a fast day coincide in the liturgical calendar, the feast is held. From any number of religious vantage points, joy is such serious business.

When I was the senior minister in settlement at my New England congregation, my favorite worship service to lead was invariably the Candlelight Christmas Eve, perhaps because the carols speak for themselves and make fairly light duty of preaching. It helps, too, that together we create that stunning visual illustration of lights shining in the darkness and not one being overtaken by the night. The carol I always printed out in the order of worship was that old English favorite, “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen”, which very rarely appears in hymnals. “Oh tidings of comfort and joy,” the carol promises, “tidings of comfort and joy.” Year round, I noticed, that’s what people came to our church for, time and time again. So in this particular holiday service, I wanted to make sure we actually gave those glad tidings to them, tidings of comfort and also tidings of joy.

These days, mainline churches and other liberal religious communities seem to find it much easier to offer comfort than joy; they are prone to lament and protest, which is of course understandable. Have you read the latest headlines? While we regularly invite people to experience desolation and then attempt to provide them some consolation, we tend not to put joy on offer. I regret that, immensely — honestly, more than I can say. I see it as a clear violation of our clerical charge and a disregard for what we owe both God and one another.

Jewish and Christian scriptures are rife with the commandment to rejoice; it appears in the Psalms and the Gospels and plenty of other places besides. Joy is absolutely a requirement for all true believers. At the historic Unitarian church I served when I was still a seminarian in New York City, we ended each worship service with a variation of the ancient priestly blessing familiar to so many of the faithful in the Church Universal; it has been lifted from the pages of Torah and translated in to our mother tongue: “The LORD God bless and keep you,” we proclaimed, “the light of God shine upon you and out from within you and be gracious unto you and grant you peace, in this and all the days you are given — may you rejoice in them and always, in one another.” Now I embrace every opportunity to dust off this trusty benediction and use it again, anywhere. Rejoice! Rejoice, already, I say.

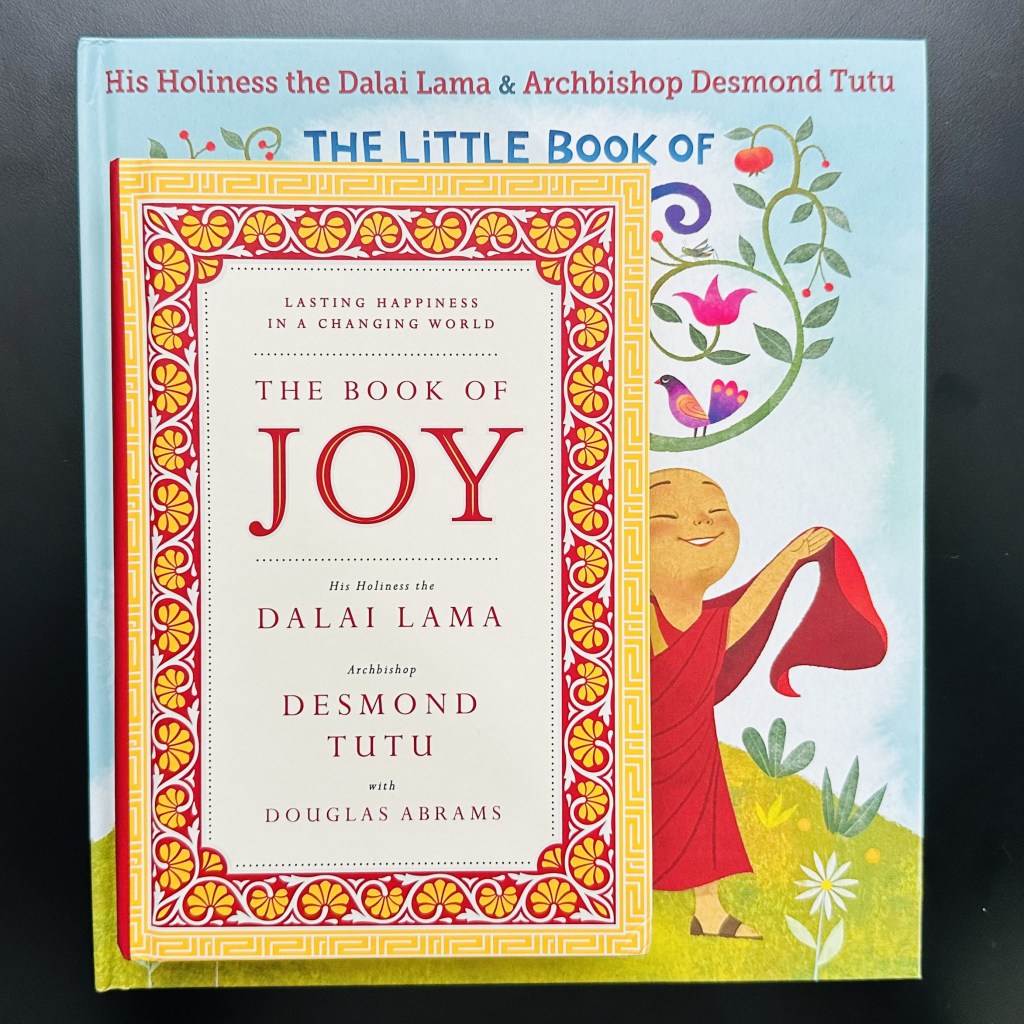

Joy is indeed your birthright, the birthright of each and every one of us. Joy is not only your birthright, but it is also arguably the most sacred duty we have been given on earth. In 2015, nearly a decade ago now, the late Archbishop Desmond Tutu travelled from this home in South Africa to India, where his dear friend the Dalai Lama was marking his 80th birthday. A Jewish author named Douglas Abrams spent several days with the two religious luminaries with the aim of writing a book that would compile their insights in to the human condition. Shortly after he published The Book of Joy: Lasting Happiness in a A Changing World, it became a best-selling title. Readers were obviously hungry for more joy in their lives, whether they were Christian or Buddhist or Jewish or some combination of those or none of the above.

In his book, Abrams contended, “we can transform joy from an ephemeral state into an enduring trait, from a fleeting feeling into a lasting way of being.” Perhaps that sounds more easily said than done, but of any number of difficult things we could potentially master, this one seems supremely worthwhile. So why not commit ourselves to such an undertaking? The Dalai Lama is fond of this revered Buddhist precept: “Always maintain only a joyful mind.” We can make joy a share priority — and we should. As Archbishop Tutu explained, “Discovery of joy does not, I’m sorry to say, save us from the inevitability of hardship and heartbreak…” he concluded. “Yet as we discover more joy, we can face suffering in a way that is ennobles rather than embitters. We have hardship without becoming hard. We have heartbreak without being heartbroken.” We may actually find our hearts broken open to, by, for one another.

In various Twelve-Step recovery programs, members of the fellowship (sometimes also known as friends of Bill or friends of Lois) will often quote this maxim to one another: “A problem shared is a problem halved and a joy shared is a joy doubled.” That multiplicative effect makes makes the close relationships we have with our friends and family, colleagues and neighbors invaluable. All of them provide us contexts where we can come together to grow our collective joy. We need to give those relationships the honor that they deserve.

In the Gospel of John, during his last supper with the disciples, Jesus calls them his “friends”and commands them to love one another as he as loved them through their years together. “If you keep my commandments, you will abide in my love,” Jesus declares. “I have said these things to you so that my joy may be in you and that your joy may be complete…” Jesus speaks to the disciples about joy with remarkable frequency in this particular gospel, more than once naming a “joy made complete.” What makes their joy complete, ultimately, is their ability to join one another in rejoicing.

In his book, Abrams notes that both Archbishop Tutu and the Dalai Lama each make the cultivation of joy central to their life of faith and are intentional about maintaining practices that make them more joyful individuals. At one point, Archbishop Tutu asks the Dalai Lama, “Why are you not morose?” The replies that he and his friend give in response to that key question quite literally fill a book. Having survived decades under apartheid in South Africa and decades in exile from occupied Tibet, they each have a firm grasp on the tragic dimension of human history. But neither believe that is the whole story. They believe we have all been given many reasons to rejoice.

Doing his part for joy, Abrams identifies the key recommendations these spiritual leaders offer to the faithful, including keeping things in perspective, finding the humor in situations, practicing humility as well as acceptance, extending forgiveness, feeling gratitude, fostering compassion, and practicing generosity. One expression of generosity is the “spiritual giving” prescribed by Buddhism. “Spiritual giving can involve giving wisdom and teachings to those who may need them,” Abrams notes, “but it can also involve helping others to be more joyful through the generosity of your own spirit.” Consider what sort of spiritual giving you might want to practice. Ask yourself: What joy can I share with others now? What joy can I invite from others? What opportunities can I find to make our communal joy feel complete?

We should all take our joy more seriously and give it the attention it is due. If we allow anything or anyone to steal our joy from us, we will have lost something essential to our human flourishing and basic vitality, a truly divine faculty of ours. That’s not the sort of defeat we ever want to sustain. We may find joy occupying the spotlight in the international arena or being touted on network television or topping the list of bestselling books less often than we’d like. All the more reason to take us that challenge Abrams issues in his book and work to transform our joy “from a fleeting feeling into a lasting way of being.” We can always make more joy room in our lives. Rejoice, already, I say! Rejoice! A little joy really does go a long way when we are intentional about keeping it in our days.

Just what I needed to read today. Thank you.