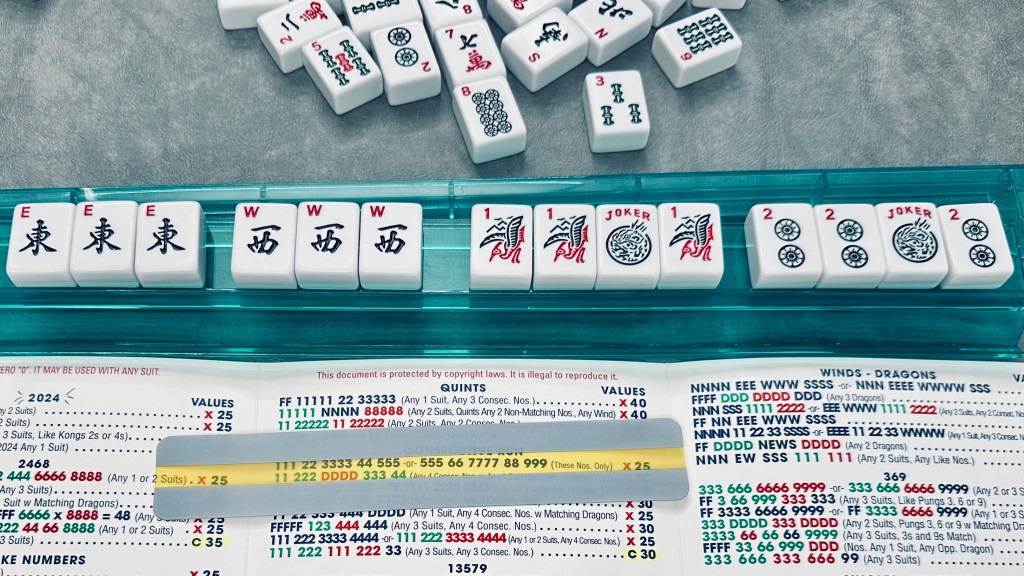

Within a week of her becoming a widow, my mother-in-law took me to play my first Mahjong game. I was accompanying her to a standing weekly game — she has two of those, for those following along at home — and she would not be the only widow playing that week. The women around the communal table had been playing each other together for decades and so picked and racked and tossed tiles at quite a clip. My mother-in-law let me watch a few rapid rounds before she placed me in her seat and invited me to join the game under her close supervision. Another player won the game before I had the chance to assemble a legitimate hand, but everyone there was a gracious loser, and I was no exception.

The rules that seemed so confusing to me then seem obvious to me now. While I have yet to become a mahjong maven, in the few months I have been playing regularly, I have become proficient. Today, I could even qualify as a respectable competitor. Mahjong is having a cultural moment all across America and the ranks of players are growing quickly and rather happily for everyone involved.

Continue reading